ADVERTISEMENT:

A nephew of Phineas, Mr Joel Tshitaudzi, still lives in Ha-Manavhela. He is the son of one of Phineas’ brothers. Here he is at the grave of his grandfather, Mapfumo Bangalia Tshitaudzi, who died in 1952.

Tracing the roots of the dreaded Panga Man back to Vhembe

Self-proclaimed prophet Paseka ‘Mboro’ Motsoeneng and his panga- and rifle-wielding bodyguards made international headlines a few weeks ago when they terrorised teachers and children at a school in Vosloorus. The name “panga man” - or sometimes “skapane” - was suddenly on the lips of people all over South Africa. But how many people still remember the most feared panga man of them all, who embarked on his reign of robberies, mayhem and terror 70 years ago?

Few people are probably aware that he came from Vhembe, where he grew up just to the south of the Soutpansberg.

Phineas Tshitaudzi is often listed as one of South Africa’s most notorious serial killers. This is not entirely accurate, as “the Panga Man” was never convicted of murder.

On the many websites and in books about mass killers he is also referred to as Phineas Tshitaundzi or even Elias Xitavhudzi. However, his real name was Phineas Munzhedzi Tshitaudzi, and he grew up in Ha-Manavhela in the Kutama area, about 35 kilometres west of Louis Trichardt. He also comes from a royal family, albeit not in South Africa.

Between 1952 and 1959, the “Panga Man” was feared in Pretoria, especially in the Fountains Valley area near a hill called Klapperkop.

His modus operandi was to wait in the dark bushes for couples who took a romantic ride along what was known as “Lover’s Lane.” When they stopped to view the city lights, he would approach the car and scrape or tap it with his machete (panga). When the driver got out to investigate the noise, he would attack, striking the man on his arms and legs with the panga, rendering him incapable of fighting back. Tshitaudzi would then assault - and often rape - the woman before fleeing.

Tshitaudzi’s ability to evade arrest gradually caused panic. Across the country, children were warned to be careful, otherwise “the Panga Man will get you.” Students were advised to avoid deserted areas and not to stop in dark or poorly lit areas.

The police launched a massive manhunt for the vicious killer but, despite several police operations to catch him, the attacks continued.

|

|

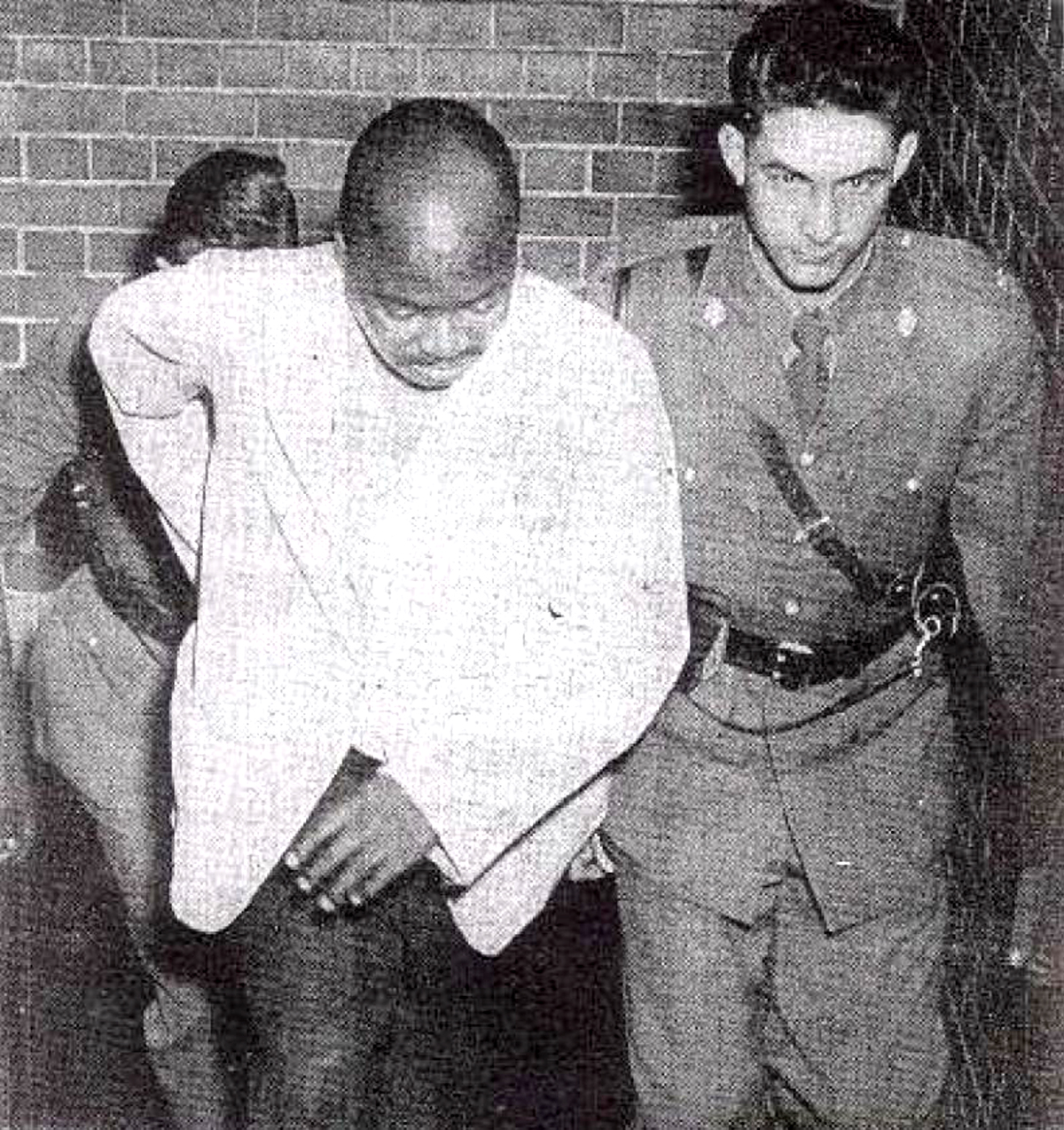

Phineas Tshitaudzi is escorted from the cells to the courts during his trial in 1960. The picture comes from one of the newspaper articles, probably that of the Vaderland. Photo: The e-Nongqai vol 4 no3. |

In Micki Pistorius’s book Strangers On The Street - Serial Homicide in South Africa, she writes that Tshitaudzi’s involvement in crime began around 1946. He was part of a gang of five robbers operating in the area south and east of Pretoria’s central business district. The group attacked and robbed people in cars and they also broke into homes. They mostly used knobkieries to scare off their victims.

“In 1952, one of the gang members, Alfred [Magatu] Malazi, was shot dead by Sergeant Jan Roux in Queenswood, and the following year, two more were arrested in the Fountains Valley and sentenced to death. A fourth member, Jack Dibakwane, was arrested in 1957 and sentenced to twelve years in prison. The last member, Phineas Tshetandizi [Tshitaudzi], became the dreaded Panga Man,” she writes.

Hunting the Panga Man

A special task force, under the leadership of Captain Fred van Niekerk, was set up, but the Panga Man continued to strike. It was as if he knew all their movements beforehand. It later transpired that Tshitaudzi worked as a cleaner and night watchman at the South African Police Headquarters in Schoeman Street, Pretoria. This allowed him to eavesdrop on the senior officers while they discussed the Panga Man investigation.

Tshitaudzi became more brazen, seemingly unconcerned that his victims could see him. An identikit was compiled, showing his round face with pop-out eyes. Miraculously, none of his victims died. They were seriously injured and maimed but lived to tell of the horror.

The Panga Man’s activities caught the attention of the media, and the Pretoria News even offered a reward for anyone who supplied information that led to his arrest. This made life more difficult for the police as amateur “detectives” began setting traps for Tshitaudzi.

The net around Tshitaudzi, known to the police as Mafuta, eventually became too tight, and on 30 September 1959, an army recruit complained to the military police that he had been assaulted by a man. The description matched that of the notorious Panga Man, and he told military police that the suspect who had attacked him might be Phineas Tshetaudzi, who worked as a night watchman at the police headquarters in Schoeman Street, Pretoria.

The information was finally passed on to Detective-Sergeant Johan Momberg, the man who had been assigned to hunt down Mafuta. Momberg devoted most of his time to finding the panga man, which included countless stake-out operations. He probed all leads, and when he heard of the panga attack on the recruit, he followed the trial.

Tshitaudzi launched his last attack on 9 October 1959. On 20 November 1959, Momberg arrested him at Wachthuis, the police headquarters. His fingerprints were taken and found to match those found at various crime scenes. When his house in Vlakfontein was searched, jewellery and other items taken from his victims were found. Hidden in a crate and covered by rags was the machete he used. Tshitaudzi confessed to the attacks.

When he appeared in court on 21 January 1960, he faced 29 charges, ranging from rape to attempted murder. Around 130 witnesses, including many of his victims, were called to testify. Some of the charges were later dropped and he was prosecuted on 14 counts.

On 6 May 1960, Justice Edwin Roper sentenced him to six years each for three charges of assault with intent to murder, four years each for two charges of assault with intent to rape, two years for assault, one year for robbery, and one year for theft. He was also sentenced to death for two rapes and three charges of assault with intent to murder and rob.

Five months later, on 14 November 1960, Tshitaudzi was taken to the gallows at Pretoria Central Prison, where he was hanged. He was only in his forties when his life, marked by violent acts, ended.

|

|

Detective Sergeant Johan Momberg arrested Tshitaudzi in November 1960. During the court hearing, he displayed the machete (panga) used to commit the crimes. |

Where Did It All Start?

Phineas Tshitaudzi grew up in a village to the west of Louis Trichardt called Ha-Manavhela. It is in the Kutama area, but unlike the adjacent, picturesque Tshikwarani (The Place in the Hills), Manavhela is flat and quite barren. A couple of kilometres away is the Mara Research station, famous for being the birthplace of the Bonsmara cattle breed.

When Limpopo Mirror visited the area, the temperature was over 30 degrees, even though it was not yet spring. The houses were modest, with a fancier double-storey house here and there. Some homes, probably those with access to a borehole, had gardens, but mostly it was just dust.

“He was a violent man, somewhat of a bully,” remembered one of the long-time residents, Mr Piet Radzilani. He grew up alongside Phineas. The home where Radzilani currently stays is a stone’s throw away from where the infamous Panga Man built his home in the 1950s. Today there is only a field where cattle graze. In around 1961 the government started to forcefully remove people to demarcated areas. When the former Venda homeland was established in the 1970s, more residents had to move. The areas where Phineas lived became agricultural land.

Radzilani recalled that Phineas Tshitaudzi was prone to drinking too much, but was not known as a thief. Local residents feared going to his house, because of his violent behaviour. But it may be that his violent outbursts only started after he had returned from war.

In 1941 Tshitaudzi was recruited, along with roughly 100 other young men from the area, to go and serve in the Native Military Corps (NMC) during World War II. He probably saw action in the North African campaign where he took part in battles such as at El Alamein. He must have returned home either late in 1945 or early in 1946, after the war had ended.

Tshitaudzi moved to the city to work after he had returned, but often came to visit on his scooter. He also brought along lots of gifts, which local residents later believed must have been the spoils of his robberies. He would send these by train, which family members would collect from the nearby Mara station or in town.

Phineas had some status in the community because of his wealth. He built a large house on a cement foundation. Prior to this, all the houses in the area had mud floors, and most were traditional huts. He also built a toilet outside his house, which was a first for the residents. He had three wives and at least two children.

When the news broke that Phineas was the infamous Panga Man, it came as a big shock to members of the community, especially his mother. By then, his father had died.

Radzilani recalled that he was on a visit to Pretoria when the trial started. He and some other young friends were performing traditional music when they heard about the court case and decided to attend. There, they met Phineas’ mother, who cried uncontrollably when she heard that her son had been sentenced to death.

Phineas Tshitaudzi’s family deliberately tried to fade into the background after the sentencing. Two of his children took on other surnames, and most moved to other areas. His three wives have all since died.

|

|

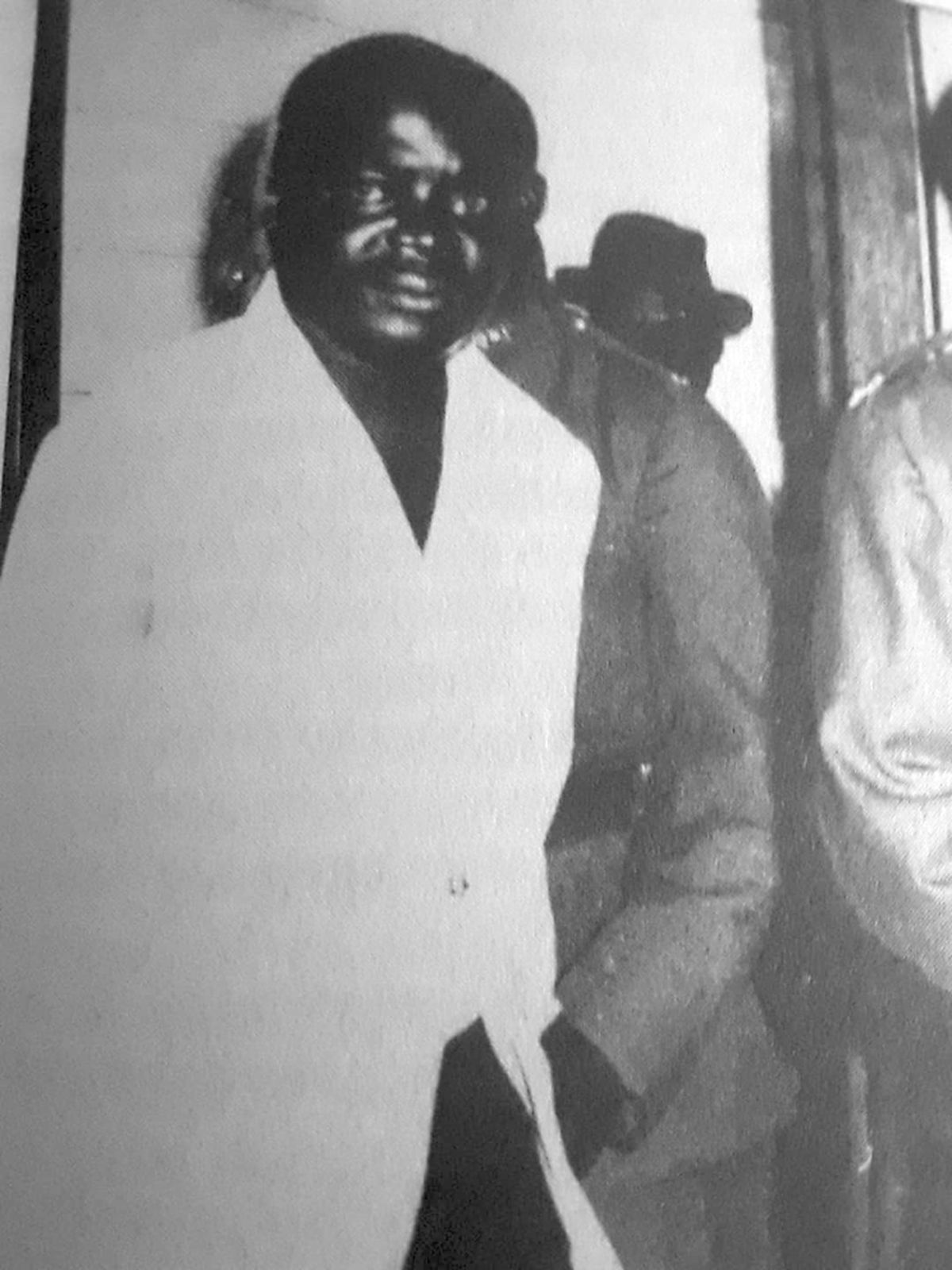

A photo of Phineas Tshitaudzi, taken during his court appearance in 1960. |

From a royal family

A nephew of Phineas, Mr Joel Tshitaudzi, still lives in Ha-Manavhela. He is the son of one of Phineas’ brothers.

“The Tshitaudzi clan is a royal family in Zimbabwe,” said Joel. He explained that his great-grandfather had moved to the region south of the Soutpansberg in the early or mid-1800s. They still maintain family ties, and he visited the royal kraal in southern Zimbabwe a few months ago.

Joel also took us to the grave of his grandfather, which is in the area where the old man lived. Today, it is only an open field where cattle graze and traces of porcupine and bushbuck can be seen.

The gravestone reads Mapfumo Bangalia Tshitaudzi and indicates that he was born on 24 November 1818 and died on 15 October 1952. Joel agreed that the 1818 birthdate must be a mistake, as it would mean his grandfather was almost 134 at the time of death. It may be that the year of birth should be 1878, but no one is certain.

The date of death is, however, interesting. The Panga Man’s violent attacks only started around the time of his father’s death.

Almost 64 years after his death, it is perhaps fitting to do a correction and get his surname correct. The main investigator in the case, D/Sgt Momberg got it right, but somehow it changed, and he was charged as Phineas Tshitaundzi. How it changed to Elias Xitavhudzi is not known.

The Panga Man’s activities brought shame upon his family. Why he did what he did, is not clear, and no-one knows what triggered his actions. It could have been that what he had witnessed during World War II, changed him forever.

Seventy years later, the name Phineas Tshitaudzi still gets mentioned at Ha-Manavhela, even if it’s just as a warning to youngsters not to engage in crime.

Sources: The e-Nongqai vol 4 no3, Facebook (Nagkantoor), Strangers On The Street - Serial Homicide in South Africa by Micki Pistorius.

Note – A paragraph had been added to the story to reflect Tshitaudzi’s war history. This was not mentioned in the newspaper article, and only came to light after publishing. We believe, however, that it is relevant to the story.

Date:24 August 2024

By: Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

Read: 5077

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT:

Sponsored Content

Living Gospel World Mission Church president calls for more help

The president of The Living Gospel World Mission Church, Pastor Robert Kharivhe, has urged members to continue honouring the legacy of the late church founder, Pastor Dr Maswole Petrus Ragimana.

ADVERTISEMENT:

Recent Articles

-

Vho Owen da Gama vhari vha na pulane khulwane na thimu ya Vondwe XI Bullets.

16 September 2024 By Frank Mavhungu -

Vho Ravhura vho ṱhaphudza pfunzo dzavho kha vhudokotela ha pfunzo.

16 September 2024 By Silas Nduvheni -

Traditional dancer Makhado says culture will not die on his watch

15 September 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo -

Another doctor's degree for former Mutale Municipality spokesperson

15 September 2024 By Silas Nduvheni -

Musician and producer Masterawylow urges fans not to give up hope

15 September 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo

ADVERTISEMENT

Popular Articles

-

Vhavenda princess' case is set to break traditional stereotypes

03 August 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

Hillary Construction to rehabilitate old N1 through Musina

22 August 2024 -

Man dies in head-on collision near Gogobole

01 August 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

From engineering dreams to fashion industry icon

25 August 2024 By Maanda Bele -

Dzanani 1 Taxi Association continues to block routes in Nzhelele

01 August 2024 By Maanda Bele -

Is Musina a gravy train for officials and councillors?

19 July 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

Tracing the roots of the dreaded Panga Man back to Vhembe

24 August 2024 By Anton van Zyl