ADVERTISEMENT:

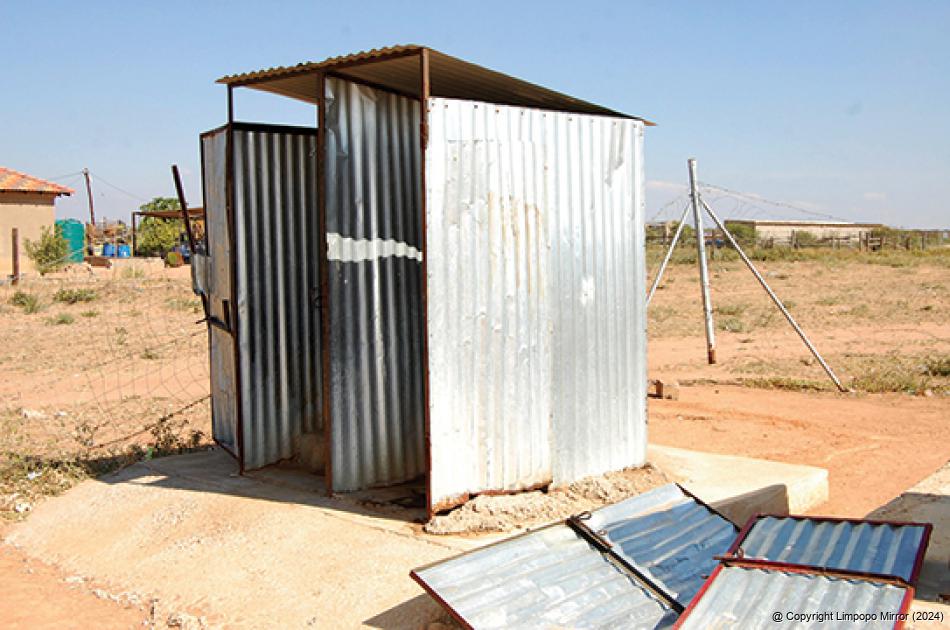

A typical example of a pit toilet at a Limpopo school. This is one of the old toilets used at Tibanefontein Primary. (Photo: Solly Masenge)

Limpopo's forgotten schools and the expensive Lottery toilets

The problem of pit toilets at schools in Limpopo is serious. The situation is so serious that pressure groups such as Section 27 had asked a High Court to force the Limpopo Department of Education (LDE) to recognise and address the problem. The court eventually ordered the LDE to conduct an audit to determine the full extent of what Section 27 describes as the province’s “forgotten schools”.

When funding is therefore made available from outside the education sector to help address this crisis, it must be welcomed. But what if a large chunk of the funding never finds its way to the targeted schools? An investigation into a R10 million grant to build new toilets in Limpopo indicates that the money could perhaps have helped restore the dignity of many more children.

How serious is the problem?

At the end of 2018, not long after president Cyril Ramaphosa launched the SAFE (Sanitation Appropriate for Education) project to tackle the problem of pit toilets at schools, the National Lotteries Commission (NLC) stepped into the arena.

According to the NLC’s spokesperson, Ndivhuho Mafela, the NLC commissioned a study, showing that in Limpopo there are “4 069 schools of which only 20% may have recently received new water and sanitation infrastructure. This translates to the fact that almost 80% of the schools still rely on old infrastructure for water and sanitation services”.

In November 2018, the NLC approved R20 million for two projects to build toilets at schools in Limpopo and the Eastern Cape. The funding was channelled through the NLC’s pro-active funding model, usually reserved for “emergency” funding. Ten Limpopo schools would benefit from the R10 million grant, according to an NLC press release. The money was channelled via a Pretoria-based non-profit company, Zibsifusion.

The figures quoted by the NLC are very dubious, although they were not the only ones battling to find out how many schools still have the dreaded pit latrines.

Early in 2018, Section 27 took the LDE to court on behalf of the parents of five-year-old Michael Komape, who drowned after falling into a dilapidated pit latrine at his school in Limpopo. The terrible incident happened in January 2014, just two months after the government had passed legislation stating that pit toilets were not allowed in South Africa’s schools. The legislation required the education department to address the problem within three years.

In November 2016, the LDE produced its Infrastructure Norms and Standards Report, quoting from research conducted by the CSIR. Section 27 later had to subpoena the CSIR to obtain the list. According to this list, 3 909 public ordinary schools existed in the province, of which 3 023 had pit toilets. A total of 889 schools had only pit toilets and eight had no sanitation facilities on the premises at all.

In April 2018, four years after Michael’s death, the judge in the Kompale case ordered the Limpopo Department of Education (LDE) to give the court “a list containing names and locations of all the schools in rural areas [of Limpopo province] with pit toilets for use by the learners”. The department handed that list to the court on August 31.

According to the LDE’s affidavit, the province has 3 752 schools, of which 1 474 still make use of pit toilets. Section 27 analysed the list and quickly spotted that it contained both duplications and omissions. The numbers differed markedly from those used by President Ramaphosa when launching the SAFE project, when he quoted figures stating that 1 360 schools with pit latrines could be found in Limpopo. Of those, 507 had only pit toilets, he said.

Section 27 decided to do its own investigation and collected data from 86 schools in Limpopo between May and July 2018 to assess their sanitation facilities. They found that nearly half (41) of the schools had unlawful pit toilets. Only 22 of the schools that Section 27 analysed were on the LDE’s August 2018 pit toilet list. “That means 19 schools with pit toilets have been left off the list,” says Section 27 on its website.

All of this might sound like a tussle about figures, but the consequences are dire. It effectively means that these schools have simply dropped off the radar and are unlikely to receive assistance soon and the dangerous and inhumane conditions that the pupils are exposed to will simply continue.

The NLC’s figures may have been thumb-sucked to justify the allocation of the grants, but the problem of pit toilets is serious – so serious, in fact, that resources cannot be wasted when trying to help.

The NLC to the rescue

On 6 November 2018, Mr Phillemon Letwaba, chief operating officer of the NLC, signed off on a grant agreement of R10 million for the “implementation of sanitation facilities in 10 public schools”. The recipient of the grant was Zibsifusion, an NPC with an address in Garstfontein, Pretoria.

Zibsifusion caught the attention of investigative journalists and an article about the toilet grant appeared in Groundup, a web-only publisher focusing on human rights issues, in March this year. It found that Zibsifusion was a typical “shelf NPC”, registered and set up by accountants and made tax compliant, before being sold as a going concern with newly appointed directors. Controversial Pretoria-based lawyer Lesley Ramulifho is a former director of Zibsifusion.

Ramulifho also claimed to be the chairperson of Denzhe Primary Care, which was the beneficiary in a R27.5-million project to build a drug rehabilitation centre near Pretoria. The project is currently under investigation and both the NLC and Denzhe have failed to explain how more than R20 million was spent.

It took several requests to get the NLC to provide details of the R10 million Limpopo schools sanitation project. Initially, a “detailed report” was promised, but it took several requests to the NLC before a PowerPoint presentation was supplied. This report turned out to be false as it contained misleading information and photos supposedly depicting “before” and “after” scenarios.

The report, compiled by Zibsifusion, also named eight schools that were supposedly to receive new toilets. Toilets at two of the schools, Tibanefontein Primary and Ncheleleng Secondary, were handed over by the NLC during ceremonies organised for that purpose.

The “handing over” of toilets at the third school, Waterval High, turned into an embarrassment when it became clear that no new toilets had been built. Instead, contractors had merely done minor refurbishments to existing toilets. Admitting that a shoddy job had been done, the handover was cancelled. Waterval High was not on the DBE’s list of schools with pit toilets.

Construction work at the other schools had either already commenced or will commence soon, according to the NLC. “The NLC anticipates the project to be completed in July 2019,” said Mafela. The LED was yet to provide the names of the two schools missing from the list of beneficiaries, he said.

Mafela did not respond to a query about why an unknown Gauteng-based NPC with no track record or experience in construction had been selected to run the project. He emphasized that the legislation allows the NLC to appoint an implementing organisation. “…implementing agents/organisations are selected after a process of consultation with a range of stakeholders, including beneficiaries of the project,” he said.

None of the Vhembe-based schools on the list that Limpopo Mirror contacted knew anything about the NLC project. The Limpopo Department of Education, however, acknowledged that they were aware that toilets were to be built.

Mafela refused to name the contractors involved in the project. “All infrastructure projects of the NLC are supervised by a panel of engineers who are technical experts in the specific field,” he said.

The NLC was previously criticised for not wanting to disclose details of professional firms involved in projects. In the case of Denzhe Primary Care, investigations revealed that a company where the brother of the NLC’s COO was the founding director, received a R15 million contract to build the Pretoria rehabilitation centre.

The cost of a toilet seat

When Section 27 took the LDE to court, the issues of costs and available funding were highlighted. It became important to establish an average “cost per seat” for building new toilets to replace the old and dangerous pit toilets.

In a detailed report compiled by Section 27, titled Towards Safe and Decent School Sanitation in Limpopo, reference is made in a footnote of a “…R50 000 per seat amount provided in the Department’s 2018 Norms and Standards Provincial Implementation Plan”.

Before even establishing the cost, one needs to first determine the type of toilets and building needed.

The NLC’s earlier statement on the sanitation project gives some guidance: “The study recommended the use of Enviro Loo type or related facilities for sanitation in the two identified provinces,” said Mafela.

The Enviro Loo toilet is a South African design that has won several international awards and is used in many countries worldwide. “The Enviro Loo is a waterless, non-polluting, low-maintenance toilet system, needing little more than the sun and some wind to operate,” states a brochure for the product.

The two schools where Zibsifusion built ablution blocks both made use of Enviro Loo systems. At both schools, two blocks containing four toilets each were constructed. The building for the boys’ toilets also included an evaporative, four-bowl urinal.

Asked about costs, the chief operating officer of Enviro Loo, Mark La Trobe, said it was extremely important that the toilets must not only be excellent in design, but also affordable. He said their design was generally less expensive than the traditional ventilated improved pit (VIP) toilet because, among other things, the overhang of the reinforced concrete slab around the tanks was much smaller.

The cost for a standard toilet, which includes the bowl and the seat, is R10 185, VAT excluded. The junior toilets are slightly more expensive, coming in at R10 309 + VAT and the four-bowl urinal costs R14 386 + VAT. At Tibanefontein Primary, the cost of the eight Enviro Loo toilets would total R90 961 + VAT. This includes all necessary pipes and brackets, as well as a two-year maintenance contract, certificates of compliance and servicing kits for two years. Enviro Loo’s representatives also train and employ a local community member to service and maintain the toilets during the life of the contract. Such a contractor can continue to service the system, once the contract has ended.

“Enviro Options [Pty] Ltd only manufactures and supplies the Enviro Loo and are not the building contractors,” said La Trobe. This means that a properly registered and accredited contractor must still demolish any of the old toilets and build new ones.

Asked about the average “per-seat” cost, based on their own experience, La Trobe said: “Some of the recent completed school projects came in at an amount of R56 000 and R77 000 (per seat) inclusive of all professional fees and the supply of the Enviro Loo,” he said.

The Department of Basic Education has also done research on costs: in its August 2018 sanitation audit it stated that the average cost per seat for Limpopo was set at R94 071. The department estimated that it would cost R918,38 million to build new toilets at 507 schools (9 412 seats) in Limpopo. This cost estimate includes construction costs, sinking and equipping boreholes, demolishing old structures and all the professional fees. Although considered a “worst-case scenario”, these estimates were used by Pres Ramaphosa during his SAFE presentation last year.

In order to get a more local and “on-the-ground” opinion, Limpopo Mirror approached a Vhembe-based building contractor, asking for a detailed quote on building two ablution blocks with an eight-seat Enviro Loo toilet setup, exactly the same as was built at Tibanefontein and Ncheleleng.

The contractor is a fully accredited builder who uses appropriate professionals to oversee its projects. The company has previous experience in such projects and the quote is a “commercial” quote, with no negotiations for discounts.

The estimate for the construction of a standard four-toilet block came to R248 802 (VAT excl.). Provision was made for 18% professional fees, a 5% contingency allowance and 22% for preliminaries. The cost per seat worked out at R62 200 (VAT excl.).

How many NLC toilets will be built?

The NLC was requested on several occasions to state how many toilets are to be built, but Mafela only replied with vague answers. The NPC, Zibsifusion, was also requested to provide us with a “cost-per-seat” estimate, but the questions were simply ignored.

The only way to try and determine the number of seats was to use the little information made available and do a guestimate.

Out of the names of the eight schools provided, one school clearly does not need new ablution facilities. The work done at Waterval High, according to a member of the school-governing body, could not have cost “more than R10 000”. At another of the schools identified, namely Tshikhovhokhovho Primary School at Khumbe village at Lwamondo, the SGB member said the school had already built toilets, using funds raised by the learners.

Apart from Waterval High, the schools identified all have between 150 and 200 learners each. These are small schools and a realistic assumption is that all of them would need similar ablution blocks to those built at Tibanefontein and Ncheleleng.

Using the local building contractor’s estimate, the two toilet blocks at each school would have cost R572 246 (VAT inclusive). Zibsifusion’s “progress report” indicated that only eight schools were to get toilets. Taking into consideration that Waterval High was merely a refurbishment project, the estimated cost is just over R4 million. Even if two more (similar) schools are added to the list, the total cost, based on the contractor’s estimate, rises to R5,2 million.

Using the Department of Basic Education’s "worst-case scenario", the cost of building such toilets at nine schools in Limpopo will be in the region of R6,77 million.

The NLC allocated R10 million to Zibsifusion to build the toilets. This works out at R138 888 per toilet seat, more than double the cost that the local contractor quoted and 47% more than the DBE’s estimate.

When the NLC’s Mafela was asked what safeguards were used to ensure that costs were realistic and market-related, he answered that the overall costing for a project was performed by the implementing organisation. “However, the NLC has ‘price-check’ type mechanisms in place to ensure that costs are not inflated,” he said.

When Mafela was pushed to supply more accurate figures on the “cost-per-seat” for the project, he responded: “The response sent to yourself is the NLC's response to your enquiry and we will request that it be quoted in full to avoid you misrepresenting our position.”

Questions about the project were sent to Louisa Mangwagape and Liesl Moses, two directors of Zibsifusion. Neither of them responded.

A visit by the National Lotteries Commission to Waterval High last month to "hand over" toilets proved quite embarrassing, as all there was to see was a rush job to try and renovate the existing buildings. (Photo: Kaizer Nengovhela)

Date:25 May 2019

By: Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

Read: 1846

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT:

Sponsored Content

McDonald’s yo rwela ṱari fulo ḽa ‘Know Our Food’

Vha McDonald’s fhano Afrika Tshipembe vho rwela ṱari fulo ḽavho ḽine ndi ḽau ḓivhadza vharengi vhavho nga ha vhuleme ha zwiḽiwa zwavho, nau ombedzela ha khamphani nga ha nḓila dzine vha dzudzanya ngayo zwiḽiwa zwavho vhatshiela vharengi.

ADVERTISEMENT:

Recent Articles

-

Township Alliance wants to assist small businesses

27 July 2024 By Silas Nduvheni -

-

Damani Water Project upgraded and handed back to waterless residents

27 July 2024 By Silas Nduvheni -

Vhafaramikovhe vhatuku vhari vha ṱoḓa masheleni murahu nau vulwa ha VBS.

26 July 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo -

Nga murahu ha minwaha ya sumbe, muḽoro wa Vendaboy Poet wo wedza.

26 July 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo

ADVERTISEMENT

Popular Articles

-

Where do Limpopo's residents move to?

16 June 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

'Vampire' who attacks old lady killed by angry mob

07 June 2024 By Maanda Bele -

Univen student to represent SA in Germany

22 June 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Light aircraft crashes at Masakona village

13 June 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Dr Tryphina explores how indigenous plants can help cure “u wela”.

15 June 2024 By Maanda Bele -

When men are together, great ideas emerge

08 June 2024 By Elmon Tshikhudo -

No, the “foreigners” are not suffocating us in Vhembe.

16 June 2024 By Anton van Zyl